When she experienced Jesus as the I AM, the Samaritan woman’s thirst was fulfilled. The “seventh man” that she met had perfected everything. She did not need the empty water jar anymore: “The woman put down her water jar and hurried back to the town…” (Jn 4:28). This was her point of conversion, which was the result of her encounter with Jesus.

After their encounter with Jesus, the magi “returned to their own country by a different way” (Mt 2:12). If they had used the same way, they would have betrayed Jesus. Peter’s reaction to his encounter with Jesus was a feeling of unworthiness, as we mentioned earlier. Jesus assured him that the journey had only begun, then “bringing their boats back to land they left everything and followed him” (Lk 5:4-11). Following Jesus is one of the common expressions of the encounter with Jesus.

Zacchaeus’ experience was expressed in his manifesto (Lk 19:8), which we have earlier discussed in detail, that had two parts: a statement of charity and an experience of “being justified.”

Conversion of Paul

One of the most powerful stories of conversion found in the New Testament is that of Saul of Tarsus. It was so powerful an event even for the early Christian community that the story is narrated at least three times in the Acts of the Apostles, two of these narrations are in the first person by Paul himself (Acts 9:1-22; 22:6-21; 26:11-20).

For me, the event of the conversion of Paul is a typical story of a “Spiritual Copernican Revolution.” [1]

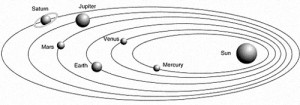

In the history of science for centuries, particularly since Ptolemy, human beings including great minds like Aristotle had always believed earth to be the centre of the universe. In what is called the geocentric cosmology, earth is the centre of the universe and all planets and stars, including the sun, move around it. But it took scientific acumen and a sense of humility to accept that earth is not centre of the universe, but that the sun was the centre of our solar system. In the heliocentric cosmology it is accepted that sun is the centre and earth moves around it. This theory was proposed by the Polish monk Copernicus, and later demonstrated by Galileo with his telescope. This paradigm shift in science is called the Copernican Revolution.

This is a very profound symbol of what happens in our own personal growth process. In the “auto-centric worldview” of my childhood I am the centre of my universe. As a baby I am showered with so much affection and attention, which makes me falsely believe that I am the centre of the universe, and everyone else in this world moves around me. While we all need this assurance to a certain degree to build a sense of self-worth, when this is exaggerated it becomes the source of my pride. This is what the Greeks called “hubris” or “hybris”.

In the Bible there are many fascinating stories of this type of hubris. Jacob was the son of his mother. Rebecca had a predilection for her younger son. (Unwittingly she was fulfilling the plan of God – Gen 25:23.) This builds a strong feminine personality in Jacob – he is a person of the indoors and is found cooking; but he develops also a strong negative anima of influencing decision-making process through manipulation and deception. This is his hubris! Jacob’s God experience at Bethal and his exposure to suffering, as we said earlier, would be the breaking up of his hubris.

On the other hand, Joseph is a son of his father. “Jacob loved Joseph more than all his other sons, for he was the son of his old age, and he had a decorated tunic made for him” (Gen 37:3). This exaggeration of the love of his father was the source of Joseph’s hubris. He was very arrogant and insensitive, which are expressions of an inflated ego. So his brothers hated him. “And they hated him even more, on account of his dreams and of what he said” (v.8). Joseph’s hubris would also be broken by suffering and being out of the security of his father’s unrealistic love.

Moses, having survived miraculously in precarious times, was a hero who had the privileges of two worlds – the care of a Hebrew mother and the opportunities created by an Egyptian mother. Moses developed a strong sense of justice and a serious sensitivity. But he was impatient and often given to violence (Ex 2:12; 17). This was his hubris. His zeal for fast solutions having recourse to violence, his fervour in defending the rights of one with no due respect for the rights of others – were perhaps also ways of hiding his inability to speak eloquently (Ex 4:10). As God would harden the heart of Pharaoh, He would break the hubris of Moses through tolerance and patience[2].

Now let us get back to our story of the conversion of Paul. Saul of Tarsus was too sure of his faith. This was his hubris. Artists often depict Saul on horseback on the way toDamascus. Saul is on horseback with his band around him, too sure of what he is up to. He is engaged in the defence of his religion. The horse being a symbol of power and control becomes also the icon of Saul’s hubris. His hubris is broken into by the ray of light. See the elements of the next scene: Saul is thrown down, a voice from heaven is heard, when he gets up he is blind, needs to be led by his servants, to a man – Ananias – who was apparently his enemy until a while ago. He is going to be told what to do. This reversal of scenes was caused by his encounter with Jesus: “For me to live is Christ” (Phil 1:21, RSV). He is now called ‘Paul’. Interestingly, this name simply means, ‘small’.

This is the Spiritual Copernican Revolution. Through a powerful God-experience in the encounter with Jesus, my hubris is broken into. I see things in the right perspective. I welcome God as the centre of my universe, knowing well that I am one of the planets going around, unique though I am. I develop now a “theo-centric” worldview. And my life becomes an interaction with others who are also trying to find their space in the universe. This is the meaning of conversion, the effect of our encounter with Jesus.

] Incidentally, even as I was thinking of this idea a few years back I came across this expression in Margaret Silf, Landmarks,London: DLT, 1998.

[2] John Sanford discusses the psychological make up of these heroes in his, The Man Who Wrestled with God: Light from the Old Testament on the Psychology of Individuation.New York: Paulist Press, 1974. He does not, however, focus on hubris.